The Haystack of Spirituality

“What drew me to this work is a desire to understand myself more clearly, but not just in an abstract or purely intellectual way. In a way that actually changes how I live, relate, and choose. I’ve spent years observing patterns in myself that I can recognize but don’t always fully master, cycles of effort and withdrawal, moments of clarity followed by old habits reasserting themselves, and a recurring sense that there’s a deeper coherence trying to emerge if I can learn how to meet it properly.”

“Most men go fishing all of their lives without knowing that it is not fish they are after.” Meher Baba’s quotation came to mind as I read through the many responses to my recent question. I had asked what you were looking for—what is the essence of your search. The answers surprised me in their precision. Here is one:

“What drew me to this work is a desire to understand myself more clearly, but not just in an abstract or purely intellectual way. In a way that actually changes how I live, relate, and choose. I’ve spent years observing patterns in myself that I can recognize but don’t always fully master, cycles of effort and withdrawal, moments of clarity followed by old habits reasserting themselves, and a recurring sense that there’s a deeper coherence trying to emerge if I can learn how to meet it properly.”

In anything we pursue, we are either drawn to something or away from something. Inner work requires some kind of balance between both drives. Dissatisfaction alone, without the belief that genuine change is possible, tips into depression. And the reverse error is equally costly: those captivated only by the promises of spiritual growth, without an honest reckoning with their low starting point, are prone to self-deception.

The reader cited above is a case in point. He is dissatisfied with the gap between what he understands and how he actually lives. Those who share this experience will recognize it all too well: our old habits disregard our better understanding. They go left when we want to go right, speak when we should remain silent, or shrink back when we know we should make an effort. The reader continues:

“I’m not seeking escape or transcendence so much as integration and how to live more consciously, with less inner friction, and with greater responsibility for my own state. What continues to draw me is the sense that this work points toward something practical and grounded as a way of working with attention, resistance, and self-observation that doesn’t bypass ordinary life, but engages it more honestly.”

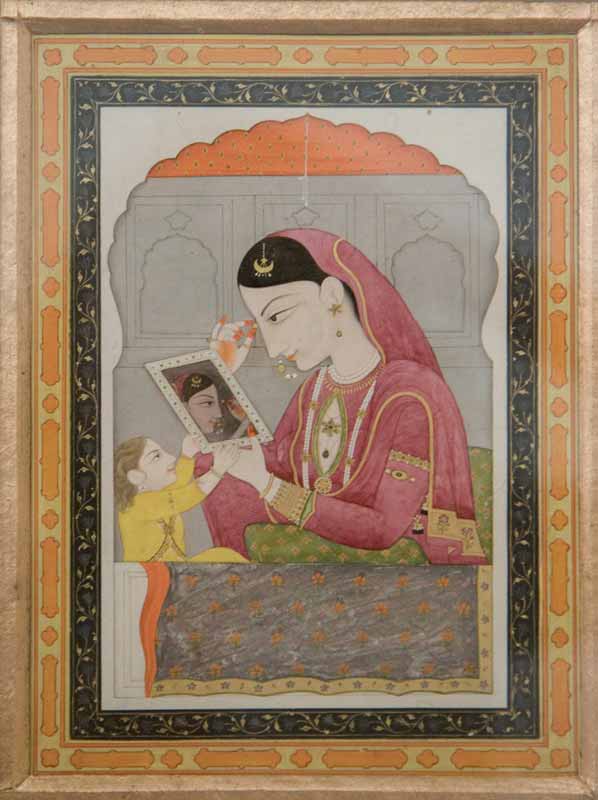

Practices that teach integration and conscious living generally fall under the umbrella of Spirituality — a problematic term, because it has grown to mean so much it has ceased meaning anything at all. Spirituality now encompasses yoga, astrology, Tarot, psychedelics, energy healing, and a plethora of other teachings and practices that readily lend themselves to escapism. The true monk is placed on equal footing with the tramp, the true believer alongside the charlatan, the true practitioner alongside the lazy idler.

But since escapism is the exact opposite of what this reader is after, how will he find the needle of integration in the giant haystack of Spirituality? Hopefully, there will be more than one such needle. Whichever it may turn out to be, it will have to strike a healthy balance between embracing the limitations of our present state and pursuing the promises of spiritual growth. Only a teaching that encompasses both can serve as a reliable guide—one that takes our present condition seriously without flattering it, and points toward genuine change without inflating it into fantasy.